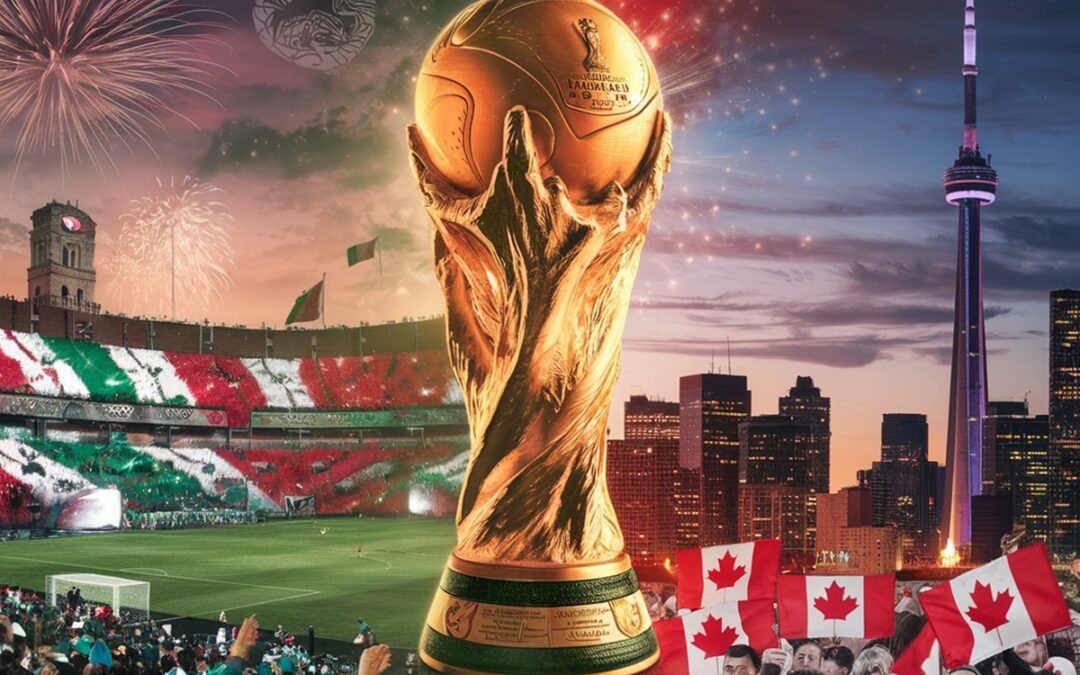

The 2026 FIFA World Cup will mark a turning point in football history. With 48 teams and 104 matches, it will be the largest tournament ever staged. The United States will host the majority of games, including the final, but Mexico and Canada will also play a key role. Each will host 13 matches, albeit with very different goals. Mexico will have the honor of kicking off the competition at the legendary Estadio Azteca, while Canada will make its debut as a men’s World Cup host.

Although the numbers place both nations in a supporting role compared to the American giant, the stories they want to tell are unique. Mexico aspires to renewal; Canada to creation. The same tournament, yet two different horizons, showing how a mega-event can adapt to such distinct national realities.

Mexico, The Power of Heritage

For Mexico, the World Cup is another chapter in a glorious history. Becoming the first country to host three World Cups places the nation on a symbolic pedestal. The Estadio Azteca, site of the opening match, will become the only stadium in the world to have staged three World Cup openers. That historic weight is no anecdote—it is the heart of Mexico’s narrative.

The ambition is to use the tournament to redefine its global image: modernize infrastructure, drive sports reforms, and present an innovative face to the world. It’s a strategy that blends pride, political calculation, and aspirations for the future.

Multi-Million Investments and Lingering Risks

Projected economic impact varies dramatically—from $500 million to $7.6 billion. At the same time, announced investments already surpass several million dollars in urban and sports infrastructure. Monterrey leads the way, with mobility and tourism projects topping 8 billion pesos. Guadalajara is modernizing its historic center, while the Azteca undergoes a $160 million-plus renovation.

The immediate impact will be seen in jobs. Monterrey expects around 7,000 direct positions, and sales in sectors like bars and restaurants could rise by 40%. However, the specter of “white elephants” hangs over every project. Whether the legacy is sustainable depends on integrating these works into urban life once the final whistle blows.

Reforming Football from Within

The World Cup is also a lever for transforming Mexico’s football structure. The Mexican Football Federation is pushing reforms that include sending young talent to Europe earlier, enforcing more playing time for under-23s in Liga MX, and raising coaching standards. The aim is to break with the reliance on low-stakes friendlies and prepare the national team for elite competition.

That technical push is reinforced by youth tournaments and the creation of an advisory council of former players and coaches. The goal is clear: leave complacency behind and consolidate Mexico as a genuine power, not just a historical one.

Related content: Canada and Mexico gain FIFA World Cup Destination Advantage

Canada, Forging a New Identity

For Canada, the World Cup is a blank page. The country has never hosted the men’s edition and sees it as a historic catalyst. Its vision is not rooted in the past but in the future: building a massive football culture to complement its traditions in hockey and basketball.

The numbers are striking: an estimated economic impact of CAD 3.8 billion and over 24,000 jobs. Yet controversy shadows the enthusiasm. Toronto and Vancouver are facing cost overruns pushing spending beyond CAD 860 million. Political pressure has forced new taxes, such as a 2.5% levy on short-term rentals in Vancouver.

Building Leagues and a Stronger National Team

At the same time, the tournament coincides with the growth of the Canadian Premier League and the 2025 launch of the Northern Super League, the country’s first professional women’s league. Both structures underpin the goal of leaving a sporting legacy far beyond July 2026.

The national team, which returned to a World Cup in 2022 after 36 years, will benefit from automatic qualification to test itself against global powerhouses and strengthen a squad determined to go beyond the group stage. The challenge is not only to play at home but to prove Canada can compete at the highest level.

Diversity as a Flag

Canada’s narrative revolves around diversity and inclusion. Toronto, one of the most multicultural cities in the world, will be the epicenter of that image. Fan Festivals and urban improvements aim to leave a tangible legacy in transport, public spaces, and community cohesion.

The risk, however, lies in public perception. If benefits do not outweigh costs, political and social pressure could tarnish the image of a progressive nation. The World Cup will test Canada’s ability to match its values with actions under the global spotlight.

Between Risks and Opportunities

Although the U.S. will host most matches, Mexico and Canada hold a strategic card: more accessible immigration policies and lower costs for international tourists. This advantage could draw more visitors than expected, amplifying benefits beyond their share of games.

The risks, however, differ. Mexico faces a race against time to complete projects, the threat of organized crime, and the need for health protocols for millions of visitors. Canada, meanwhile, struggles with cost overruns, potential environmental impacts such as wildfires, and safety concerns at stadiums.

Two Paths, One World Cup

The legacy will not be uniform. For Mexico, success will be measured by its ability to modernize infrastructure, reform football, and project a renewed national brand. For Canada, the goal is to grow a sport, consolidate professional leagues, and showcase a diverse and open society to the world.

On July 19, 2026, when the final is played in New Jersey, the largest tournament in history will end. But it will also mark the beginning of a new era for two countries that, with different perspectives, found in the same event an opportunity to transform themselves forever.